Gender-specific differences

Gender medicine: Why is good healthcare not a matter of course for everyone?

Gender medicine is the study of gender-specific health differences. Many diseases manifest themselves differently in men and women and therapies do not always have the same effect depending on the sex of the patient being treated. However, there is currently not enough data on these differences. Research teams including the one led by Professor Dr. Dr. Sonja Loges from the University Medical Centre Mannheim and the German Cancer Research Center are seeking to change this.

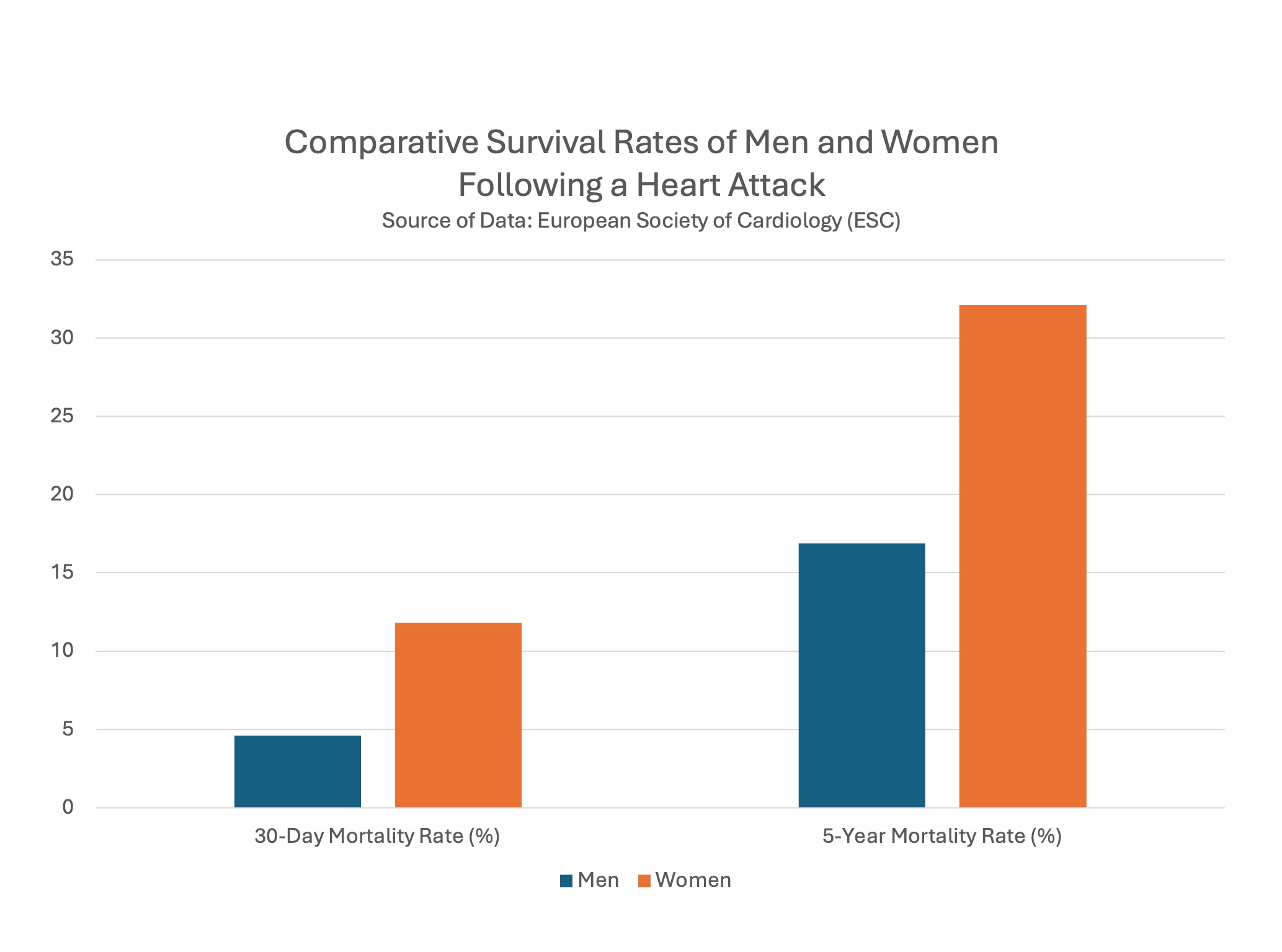

Even today, women are between two and three times more likely to die from a heart attack than men and are hospitalised later, as a 2023 study by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) shows (1). Even after adjusting for various risk factors, the study found that 11.8% of women had died after 30 days compared to 4.6% of men. After five years, 32.1 % of women had died compared to 16.9 % of men. © Dr. Anja Segschneider

Even today, women are between two and three times more likely to die from a heart attack than men and are hospitalised later, as a 2023 study by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) shows (1). Even after adjusting for various risk factors, the study found that 11.8% of women had died after 30 days compared to 4.6% of men. After five years, 32.1 % of women had died compared to 16.9 % of men. © Dr. Anja SegschneiderIn the 1980s, the American cardiologist Marianne J. Legato made a discovery that completely astounded her: many of her female heart attack patients did not display the typical symptoms such as pain in the chest and arms. Their symptoms tended to be sweating, nausea and back, head and neck pain. As a result, doctors sometimes dismissed life-threatening conditions in women and simply sent them home again – often with fatal outcome. Legato was shocked. She began to think that women with heart disease displayed completely different symptoms to men. And if this was the case, why were trained doctors unaware of this? Legato had found her new speciality. Today, she is considered one of the founders of gender medicine.2)

Decades later, it has become clear how fundamentally different the male and female bodies actually are. These differences go far beyond sexual organs and hormones. Women and men often react completely differently to medication and therapies. Disease progression and symptoms are sometimes totally different. Nevertheless, even today, only in exceptional cases are these male/female differences taken into consideration in diagnostics and drug prescriptions.

Therapies need to be adapted to gender

Prof. Dr. Dr. Sonja Loges, Medical Director of the Personalised Oncology Department at the University Medical Centre Mannheim (UMM) & the DKFZ Hector Cancer Institute and Head of the Personalised Medical Oncology Department at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). © Photo, graphics and video center University Medical Center Mannheim (UMM)

Prof. Dr. Dr. Sonja Loges, who is Medical Director of the Personalised Oncology Department at the University Medical Centre Mannheim (UMM) & the DKFZ Hector Cancer Institute as well as Head of the Personalised Medical Oncology Department at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), knows only too well how differently therapies actually work in men and women. One of her areas of research is immunotherapy for treating certain forms of lung cancer that involves rebooting the patient's immune system so it can fight the tumours on its own. There are high hopes for this procedure when it comes to treating many seriously ill patients. But as Loges says: "It came to my attention that hardly any women took part in one of the large pivotal clinical trials undertaken to obtain the marketing approval for a new immunotherapy for lung cancer." She did some research and found out that although the therapy was effective in men, there was no survival advantage for women compared to chemotherapy. In other words, the immunotherapy in its current form was not as effective for female patients as it was for male patients. "Nevertheless, the drug is also approved for women," says Loges.

"Such inconsistencies also occur the other way round," says Loges. In the case of a drug for lymph node cancer, for example, it only became apparent years later that the recommended dose for men over 65 should actually be considerably higher. Women were overrepresented in the pivotal clinical trials. Such discrepancies exist in a number of areas: women have a more active immune system and are therefore more likely to suffer from autoimmune diseases whereas men are more severely affected by coronavirus. In women, ADHD3) or autism4) are often not recognised because they are considered ‘men's diseases’. In contrast, depression is often diagnosed far too late in men because they display different symptoms to women. Recognising gender differences in treatment would therefore help everyone.

There is too little data on medical gender differences

But why do some diseases look so different in men and women? And why in some cases do they react differently to medication? Hormones are often cited as the cause, but that is probably not the only reason. It is not an easy question to answer. "The problem is that we simply lack data," says Loges, referring to the so-called gender data gap, i.e., a lack of study data that explicitly differentiates between the sexes or deals specifically with women.

Research is male, which means there is more data that applies to men. Animal experiments are predominantly carried out on male animals. Men are disproportionately represented in clinical trials involving humans. The data collected for men is then simply transferred to women. This is often justified on the grounds that the female menstrual cycle makes research too complicated and expensive. However, Loges takes a critical view of this argument: "New therapies are also approved for women regardless of their menstrual cycle."

So why are women really underrepresented in clinical trials? This question cannot be answered either due to lack of data. "Are doctors in some way responsible for this? Or is it down to the trial participants? Are women perhaps more sceptical?" says Loges. She and her team would like to help close the gender data gap in medicine. Loges is part of a research group on sex differences in the immune system (Research Unit 5068: ‘Sex differences in immunity’)5) funded by the German Research Foundation and is planning another project to determine why women are so often underrepresented in clinical trials.

The road to good healthcare for all is a rocky one

However, making medicine fairer is not that easy, it seems. Scientists working in the field of gender-specific medicine still complain that their research is often not taken seriously or dismissed as irrelevant.6) The first independent institute for gender-sensitive medicine in Germany was only established in 2007, at Berlin’s Charité hospital. Its founder, Prof. Dr. Dr. Vera Regitz-Zagrosek, told the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung that she has had to fight against considerable prejudice in her field of research.7)

Women in the healthcare sector also struggle to reach positions where they could counteract such prejudices. A 2020 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) concluded that the proportion of women in management positions in medicine is actually falling and stands at just 29 percent. According to the German Medical Women's Association, the figure for female senior managers at university hospitals was only 18 percent in 2022. Female patients also have to contend with prejudice and are often not taken seriously by doctors, especially when they show symptoms that appear to be atypical of a particular disease.8)

This is often due to gaps in knowledge as gender medicine research results are only gradually finding their way into practice. A 2020 report by the German Society for Gender-Specific Medicine9) came to the conclusion that only 56 to 70 percent of the German universities surveyed addressed gender and diversity issues in their courses and just 3.7 percent of faculties covered gender issues across the curriculum with examination relevance.

How can medicine be made fairer?

Loges is convinced that a change in legislation will eventually be needed, especially in the area of clinical trials. Equal consideration should be given to women and men, and gender differentiation should be applied. Some progress has already been made in recent years, particularly in Europe, with new regulations such as the Clinical Trials Regulation (CTR). However, CTR requirements regarding the representative composition of cohorts are still very vaguely formulated and do not have to be taken into account if so stipulated by the trial protocol. Stricter laws could help here. But regardless of how gender-specific medicine is ultimately implemented in practice, it can save lives - and ultimately benefits everyone.